Research conducted by Levin Sources in Zimbabwe shows that the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated pre-existing challenges associated with a recent period of economic, social and political fragility.

About the Delve COVID-19 Impact Reporting initiative

In June, we launched a research effort into the impacts of COVID-19 on artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) communities in Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Uganda and the DRC, as part of a global data collection exercise on the topic. The research is funded by the World Bank’s Extractives Global Programmatic Support Multi-Donor Trust Fund and coordinated through the Delve COVID-19 Impact Reporting initiative, which covers 22 countries.

This blog presents seven key findings from the data collected in Zimbabwe as well as recommendations for mitigating the negative impacts identified. Between June and July 2020, data was collected through interviews with thirty representatives from mining communities in the Midlands and Matabeleland South provinces, who were interviewed five times over a period of ten weeks. An additional thirteen key stakeholders in the ASM gold sector, including local and international NGOs, the miners’ federation, governmental institutions and local miners’ associations, provided expert opinions.

1 - COVID-19 has exacerbated an already complex situation

In recent years, Zimbabwe has suffered repetitive droughts, high inflation, and foreign exchange shortages leading to a weakened economy and natural disasters such as Cyclone IDAI in 2019. On top of this, the COVID-19 pandemic is predicted to undermine economic forecasts for 2020[OL1] . This will likely result in stagnation as macroeconomic policies will have to be balanced with emergency needs. It may also lead to negative social impacts such as increased food insecurity, job losses in sectors such as tourism, reduced trade of goods and services, decreased remittances and potential risks to vulnerable groups, such women and girls. Moreover, Zimbabwe’s economy is highly informal , reducing the coverage and effectiveness of social security systems which could provide emergency support to the most vulnerable during the COVID-19 pandemic. ASM communities are particularly exposed to these impacts – many live hand-to-mouth and with limited savings. Given that the sector is often relied upon to provide emergency income during economic shocks, it is essential that the needs of ASM communities are taken into account as the pandemic evolves.

2 – Food insecurity has increased

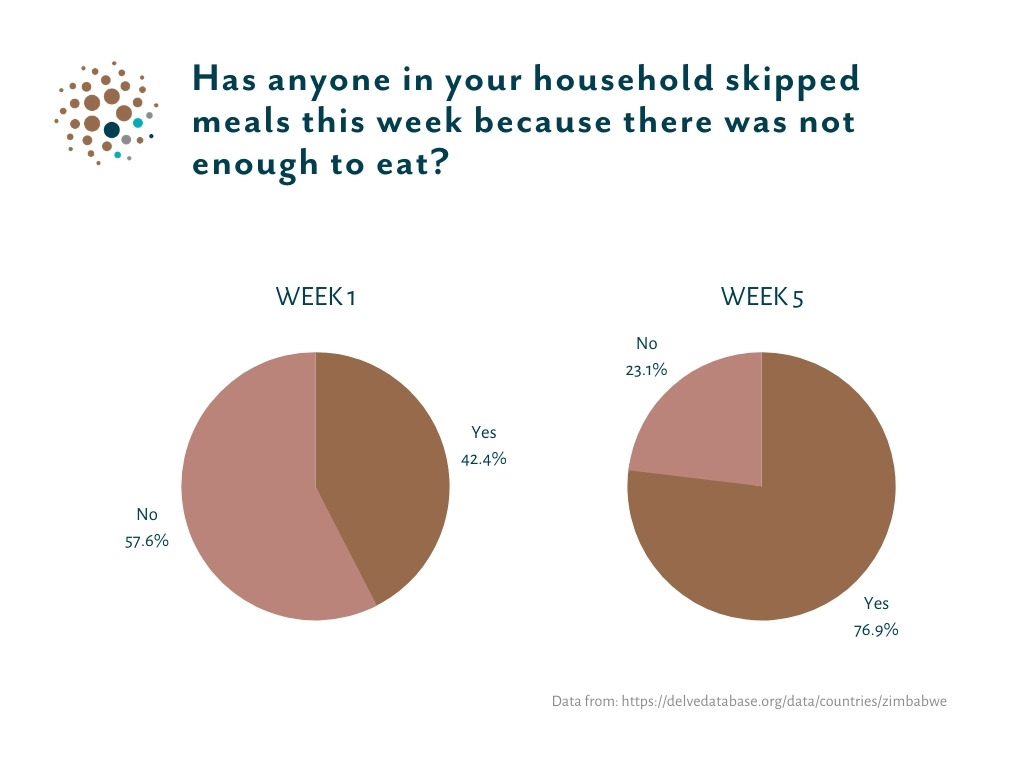

Food insecurity has become widespread since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic – interviews with both miners and key stakeholders confirm challenges in meeting basic nutrition needs. When COVID-19 hit Zimbabwe, the country had already been experiencing one of the worst food crises in living memory, made worse by changing weather patterns such as increased drought, as well as economic crises linked to shortages of cash, high inflation and challenges in the supply of fuel and power. The onset of the pandemic appears to have intensified this food crisis. Despite being recognised as an essential activity and exempt from lockdown restrictions, agricultural production has been suffering during the pandemic, due in part to worsening access to finance and agricultural inputs. The availability and distribution of supplies (food products and agricultural inputs) in country has been disrupted. Study respondents cited examples of people queuing all day to access basic goods. At some ASM sites, managers have allocated one person to queue in order to provide food to workers. In addition, prices have risen, cash availability has worsened, and household income has declined due to rising unemployment. Many respondents in ASM communities, especially those who were laid off during the COVID-19 crisis, expressed difficulties in buying enough food and have had to skip meals frequently, a trend that worsened as the pandemic progressed – the proportion of respondents who reported that someone in their household skipped meals because there was not enough to eat increased from 42% in May to 77% in July. In response, the government, as well as some NGOs, were reportedly distributing essential food items to vulnerable families, however it was difficult to ascertain whether this support was sufficient and systematic.

3 – ASM gold production and sales have declined

Production of ASM gold and sales to Fidelity Printers and Refiners (FPR), the sole legal buyer of gold in Zimbabwe, have declined. A number of reported reasons for this are outlined below.

First, government lockdown measures and movement restrictions aimed at containing the spread of the virus resulted in reduced workforces at ASM gold sites, leaving many unable to earn an income and leading to a reduction in production. Our research indicated that these impacts disproportionately affected women, a phenomenon that we have explored in a previous article. Following advocacy efforts from the Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association (ZELA) and the Zimbabwe Miners Federation, the government recognised the ASM sector as an essential activity, allowing registered miners to receive transport permits to travel to their work locations. However, the requirement for miners to be registered proved to be a barrier to effective implementation of the policy. An estimated 84% of miners in Zimbabwe are unregistered, leaving many unable to travel to mine sites under pandemic rules. Respondents without travel permits also reported challenges in accessing FPR agents to sell their gold. Despite these constraints, it is likely that the ASM sector will present an increasingly attractive opportunity for many, given the lack of alternative available livelihoods and the appeal of receiving income in USD (FPR pays miners in foreign currency).

Secondly, ASM operators faced increased challenges in accessing tools, inputs and equipment for production. For instance, it was reported that the price of mercury increased in some provinces. Whilst this could represent an opportunity in the long-run for the uptake of safer and less environmentally damaging gold processing techniques, it results in the short term in negative impacts for miners (especially women, who play an important role in gold processing), who experience higher costs of production and smaller margins. Similarly, a scarcity of fuel – necessary to operate mining machinery – has slowed down production.

Third, research participants have reported delays in cash payments from FPR, to whom the majority continue to sell their gold. These delays have not only left producers with less income, but have also increased the risk of gold being diverted to the parallel illicit market. Illegitimate buyers can make prompt cash payments, which in times of crisis, is essential.

Reduced gold production is likely to adversely affect both the local and national economy. The gold sector is an important source of foreign currency which can boost capacity for imports at the national level as well as providing livelihood and income stability for individuals in the context of persistent local currency inflation.

4 – The pandemic has increased the risk of child labour

Survey responses suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic could lead to impacts on children in ASM communities. Besides experiencing reduced food availability, school closures have reportedly resulted in children being left at home alone, particularly if parents – especially women – had to spend several days at mine sites due to movement restrictions. Reports of children accompanying their parents to sites have also increased. Although the presence of children at mines sites does not imply direct involvement in mining work, the current fragile economic and social context, including reduced income for many families, suggests that there are increased risks of child labour. Recent statements from local environmentalist watchdog ZELA reinforce concerns about children’s engagement in mining activity.

5 – Theft at mine sites has increased, but not violence

Anecdotal evidence from interviews present a mixed picture on human security. Some provinces of Zimbabwe, including those surveyed for our research, had been recording episodes of violence in mining communities. These so-called ’machete attacks‘ – already prevalent in some provinces – were being reported for several months in increased intensity before COVID-19. Since the onset of the pandemic, most respondents reported that the attacks have reduced in number, potentially due to transport restrictions and the increased presence of police around mine sites to control the movement of people. Conversely, respondents have reported an increase in the theft of equipment and material from mine sites, likely driven by increased economic insecurity and a reduced presence of workers at mine sites, giving rise to opportunism. The increase in theft marks a worrying trend that could impact future sectoral recovery efforts.

6 – The pandemic has brought to light some of the failures of COVID-related policy to account for ASM-specific needs

While awareness-raising has been conducted in ASM communities by government agencies, NGOs and telephone service providers, effective implementation of preventive measures has been hindered by a number of challenges.

The risk of transmission of coronavirus in ASM gold communities is material, given the labour-intensive nature of activities and movement between sites by traders and other service providers. Despite this, our research shows that the preventive measures imposed upon ASM communities have not generally been sufficiently adapted to the ASM gold context. Hand sanitiser, for example, has been touted as an effective measure to prevent the spread of the virus. However, hand sanitisers are expensive, and most miners are not able to afford the required quantities. Moreover, they are also impractical and less effective as miners work with soil. Hand washing stations could represent an alternative to hand sanitizers, although reports stated that access to water around mine sites can also be challenging. It was also reported that testing for Covid-19 at mine sites was limited, noting that equipment for testing and temperature screening are expensive for ASM operators.

7 – ASM communities have shown innovation and resilience in the face of challenges brought on by the pandemic

Despite the challenges faced by ASM communities in implementing preventive measures, some respondents shared examples of local, ASM-specific initiatives to combat the spread of the pandemic. Examples include the local production of homemade hand sanitisers and cloth masks using recycled clothes. In Shurugwi, the community went as far as to set up an isolation centre for ASM miners in a local hospital, organising to raise funds for beds, PPE and separate spaces for female and male miners. These examples demonstrate that ASM communities are doing what they can to protect themselves, in a context where access to adequate healthcare is lacking and where there is limited guidance on what constitutes appropriate PPE and other safety requirements.

What can and should be done to better respond to the impacts of COVID-19?

Data collected shows that COVID-19 and its associated restrictions on movement, mine site access and trade have had significant direct and indirect impacts on ASM communities in Zimbabwe. s increased food insecurity, a sustained reduction in incomes for the majority of ASM households, a decline in ASM gold production, a lack of data on cases of COVID-19 among ASM communities and limited implementation of health and safety measures at ASM sites. Addressing these and other impacts will be key in ensuring a strong post-COVID recovery in Zimbabwe. Acknowledging that many of the issues mentioned above are associated with pre-existing socio-economic and political trends, the list below suggests potential strategies to mitigate some of the negative impacts of the pandemic on ASM communities, while building longer-term solutions to more systemic challenges.

- Adapting COVID-19 measures to the ASM gold sector should be considered to complement awareness-raising efforts and ensuring that the implementation of prevention measures is feasible for ASM communities. This will include addressing difficulties in accessing PPE for miners and the lack of handwashing infrastructure or alternatives where water is not available.

- Training and awareness-raising efforts should be continued to ensure they reach as many communities as possible. The content of these activities should be properly translated into the language understood and spoken by target communities. There is also need for specific messages and discussion platforms on COVID-19 Standard Operation Procedures for ASM operations.

- Testing should be supported in ASM communities.

- Access to FPR buying agents should be facilitated, ensuring that regardless of travel restrictions or unavailability of funds for transport, mines can continue to sell gold through official channels.

- Formalisation should be promoted at mine site level as well as along the supply chain. This could support trust-building between government and mine-site stakeholders, with the government being able to demonstrate value to the local population by keeping mines open and safe through the roll-out of COVID-19 Standard Operation Procedures, increased implementation of preventive measures and reduction or mitigation of negative impacts.