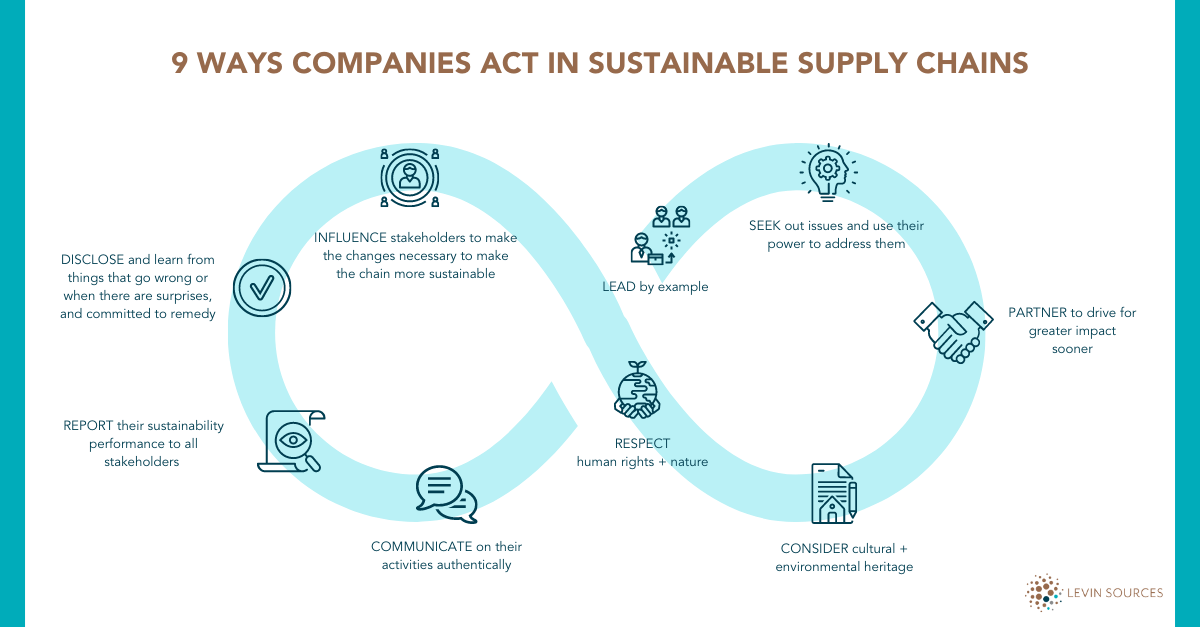

“In sustainable supply chains, companies…Lead by example. Partner to drive for greater impact sooner. Are fundamentally curious and innovative, seeking out issues and using their power to address them.”

Monique Lempers, Impact Innovation Director at Fairphone, puts a fine point on the relevance of partnership in supply chain sustainability: “When I look back at the key moments where we wanted to address risks or find solutions to the challenges that we encountered, we always had a partner or always needed to find a partner. Things are almost never done by just us; we simply don't have that leverage.”

At Levin Sources, we lean into the need for partnership and collaboration. A signature of our work is our ability to convene industry-specific expertise that operates at the intersection of the public and private spheres or from one end of the supply chain with the other. To have relationships and ongoing collaborations with individuals, organisations, and governments across the space, allowing us to understand our work within the broader context and - to Lempers’ point - work with and within these relationships and structures to effect change.

In our next blog, we’ll dig into how relationships and leverage work for companies across their supply chain, particularly with SMEs. Ahead of that, I want to zoom out to the broader governance picture, as it is instructive of the context in which relationships work.

When a company thinks about increasing the sustainability of its supply chains, the impact and importance of government and civil society engagement can’t be overstated. Government and civil society are critical partners and key enablers of supply chain sustainability.

Since its founding, Levin Sources has been working with companies in, and connected via, supply chains to the Great Lakes region of Africa.

Our two decades of experience in the Great Lakes region and in the supply chains that radiate out informs our thinking on engagement with government and civil society.

The community of stakeholders around our work is complex and broad. This includes the governments of the DRC and the adjoining countries who are investing in creating the conditions to make more responsible sourcing possible.

Meanwhile, the rapid changes over the course of the last decade simply couldn't have been possible without the political will, legal frameworks and requirements, and millions invested by European and North American governments.

This is important because the reality is that systemic problems require systemic solutions. Supply chain sustainability work inevitably requires companies to involve and engage with different players in the system. Engagement means taking risk, but a critical focus of our work at Levin Sources is to use due diligence processes and systems not to omit risk entirely—even if that were possible—but to understand it, recognize it, reduce it, manage it.

Fairphone’s legacy is instructive here as it includes an intentional choice to engage rather than disengage, partner rather than disassociate.

Following the 2008 financial crash, the U.S. government passed a massive piece of legislation called the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act, mostly focused on reforming the banking and investment sectors. Section 1502, however, amended the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 and brought a focus to mineral supply chains containing tin, tantalum, tungsten or gold (3TGs). These so-called “conflict minerals” had been found to support armed conflict and human rights abuses when sourced from the DRC and surrounding countries. Section 1502 established a requirement for publicly traded companies to file a specialised disclosure document, known as Form SD, if 3TGs were found to be “necessary to the functionality or production” of a product manufactured or contracted to be manufactured by the company.

The regulations sparked a global reckoning with global supply chains so opaque that it was difficult to determine the source of their 3TG minerals at all, never mind if they were linked to conflict or serious human rights abuses.

Companies around the world—not just in America—were suddenly asked to disclose the source and chain of custody of their 3TGs, which meant they would now need to track and trace what minerals they were using, where they were sourcing those minerals from, and whether or not they could have financed armed groups in that region.

As Lempers describes Fairphone’s journey, “And, well, yeah, [companies] found the minerals could in some case be coming from conflict areas, including the DRC and the surrounding countries.”

What is so compelling to us at Levin Source is what Lempers said next about risk. She mindfully zooms out to recognise a fuller picture of risk. Not just the reputational risk to a U.S. company who must now make a public report, but also the network of risks created should companies totally divest from the Great Lakes region or the government institute a permanent ban on exportation of minerals.

“You can still source conflict free minerals, or tin in this case, from areas where people really need the income, and therefore the risky areas, that now everyone was avoiding.” Lempers explained.

Specifically, Fairphone looked at the risk all the communities that were depending on their incomes from mining would face of going from one day to another without income. In the risk they saw an opportunity.

Levin Sources, and thousands of other organisations, companies, not-for-profits, ranging from Global Witness to Apple made the same calculation and choice: instead of choosing to disengage, we choose collaboration and partnership.

One of these hubs for partnership and engagement in the Great Lakes Region was the Conflict-Free Tin Initiative, which was at the time also supported by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands, Philips, Tata Steel, Fairphone, and many others. This coalition of governments, civil society, and private companies joined together to show that disengagement was not the only path. It was still possible to set up a track and trace system that could guarantee responsible sourcing of conflict-free minerals from the area, including an area that was identified as high risk.

This initiative was by no means the only one. Government, civil society, and private business worked together to build a whole big system which allowed industry to source from that risky area. Meaning real incomes and livelihoods for some of the world’s most vulnerable people.

The key decision point was the choice early on and then reaffirmed on a near-daily basis to engage rather than disengage.

The work in the Great Lakes region is ongoing, and truly global in scale, requiring constantly evolving partnerships, collaboration, and communication most recently continued for Levin Sources in the form of USAID's Zahabu Safi (Clean Gold) Project.

The point, the choice, and the lessons are applicable to every company working to improve the sustainability of their supply chain: engage rather than disengage, partner, and communicate to create necessary leverage.

“That is the type of role we try to play.” Lempers concludes, “We try to go where it is risky, to find scalable solutions within collaboration with others, and then hope that the broader industry also picks it up or follows it.”

In other words, leadership means never going at it alone.