Last year, Levin Sources was invited to contribute to the European SGD Summit 2020, organised by CSR Europe, and to take part at the roundtable on raw materials for the automotive sector and the development challenges related to mining. The request was to speak about what is needed to advance the agenda on driving impact in mineral supply chains and supporting development in producer communities and countries.

Unfortunately, the round table could not take place due to technical issues. But this blog is a synthesis of the key points we wanted to make, what we see as driving change, as well as of some of the remaining barriers and what more is needed in the future, if we are serious about achieving the SDGs.

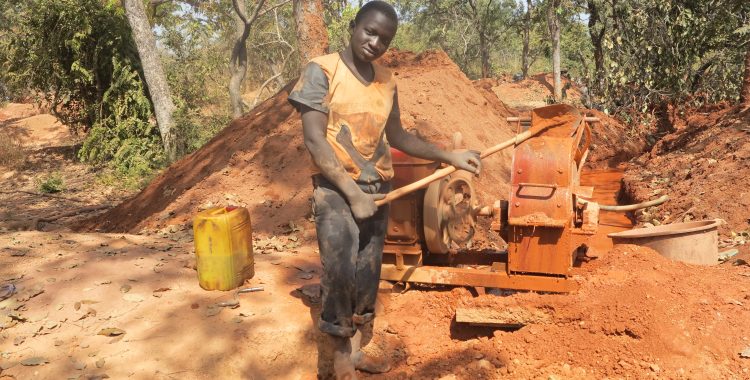

We took the example of artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) in mineral supply chains to illustrate our points. This is because we see ASM as one of the areas where mid- and downstream companies can help drive change, and the below draws on the experience of some of our up-, mid- and downstream clients.

What is driving change already?

1. Market pressure and incentives

One of the biggest leverage points and opportunities for impact by downstream companies is their supply chain, and the demands they make of their suppliers. Downstream companies can use their power as the market for producers to drive change. Levin Sources has seen industrial miners suddenly accelerating to address issues when they sign a contract with a downstream customer who has a solid due diligence framework. Of course, this is more difficult for ASM and small producers, as they typically are not dependent on larger contracts or ‘responsible’ buyers, and often are less able to implement changes alone. But if we manage to design models with incentives, where ASM producers see market advantages to improve, change will be incentivised. Regulatory pressures and requirements can influence this indirectly, but the change accelerates once the buyers, the market and the downstream companies require and foster it.

2. Recognition that disengagement is counterproductive

We increasingly see mid- and downstream companies and clients who proactively want to include ASM producers in their value chains. This is because they see this as a good way to drive change on the ground. For many of these companies, this choice is not yet commercially viable, and it requires a lot of time and investment. But they do it because a) they recognise the positive impact they can have in ASM communities, and b) that ASM producers could become a viable source over time. Rather than saying: ‘We do not buy from ASM because it has so many issues (and therefore we have a clean vest)’, these companies say: ‘We do buy from ASM because we can help improve their situation through market-based incentives.’

3. Escalator models / modular benchmarks

We are seeing a movement that goes away from so called ‘best in class benchmarks’, where a producer has to invest and work for a long time to be able to reach a very high benchmark (such as a certification) and only then can start selling their product. Now standard frameworks are being developed that are modular, or use so called ‘escalator models’ – where engagement with and buying from the producer starts already at a relatively low level of responsibility, but with the condition that the producer improves over time, and with structures to support them in this. In some models, such as the Better Gold Initiative (BGI), the ASM producers receive additional benefits for improvement (a premium) beyond the access to markets. Such models take ASM producers on a journey, and has helped driving them to improve.

4. Transparency, pro-active and nuanced communication

For a long time, we have seen a tendency for downstream companies to put their head down if they were the focus of accusations or advocacy campaigns. This ostrich response isn’t helpful because it leads to an unnuanced understanding also by consumers, who often have difficulties making sense of the challenges and dilemmas companies are facing in their supply chain. But increasingly, mid and downstream companies are proactively communicating on what they do. Even more importantly, they do so not in a glossy, green-washing way, but they openly talk about the challenges and difficulties. They transparently show what they have been trying to do, and where they have not yet been able to achieve what they wanted, and give reasons for that – including that other actors/governments are needed to change things. We have seen that this contributes to a more nuanced discussion about what is possible, pragmatic solutions, and helps consumers understand the issues better.

What barriers remain – what more is needed?

1. From islands of excellence to broader changes in producer countries

We are seeing a lot of supply chain initiatives aiming at integrating ASM into their supply chains and doing important and much-needed work to improve the conditions and practices at ASM sites. While these are great achievements, there is a risk of creating 'islands of excellence', where a few specific ASM mine sites are lifted up, supported and manage to achieve certain standards, but where the large majority of the sector remains untackled. We need to start thinking about how we can bring about change at the sectoral level, and in whole geographies, areas, countries, rather than for a few best in class champions. This is certainly not an easy task, and will take more and longer efforts, and certainly cannot be the task of downstream companies alone.

2. From disregarding the responsibility and role of Governments to recognising companies’ spheres of influence and ensuring that Governments play a key role

Many of the current initiatives are led by the private sector, downstream companies or industry associations. While some of them are truly multi-partite and use multi-stakeholder approaches, others tend to involve the host nation’s Government only marginally. This is often well intentioned, but we need to recognise (and communicate!) that downstream companies cannot and should not solve all problems alone. Most of the issues connected with ASM (child labour, informality, etc) have structural, systemic root causes, such as poverty, unemployment, governance, state capacities. The responsibility to address these also (and mainly) lie with Governments. Therefore, it is crucial to involve and collaborate with producer nation Governments instead of bypassing them; to support them in managing the sector, ensure they have the capacities and resources to do so. Otherwise we will not solve these issues in a sustainable manner. Development agencies and donors can play a crucial role in this.

3. Moving towards inclusion in supply chains from a low level

Numerous mineral supply chains initiatives have been attempting to define what ‘responsible’ looks like. Some of these processes have focussed on benchmarking best practices mainly, with a ‘certification view’ at their core: “we can source from there once they achieve this benchmark”. While this is not wrong, this approach can present a barrier and disincentive for ASM or other small producers. It can take years and a lot of investment until such benchmarks are reached, and in the meantime, people need to be able to sell their product and make a living. ASM producers therefore continue selling into informal channels, and may not see a reason to change because the effort to reach the benchmark is so huge. This means that investments in achieving benchmarks should come with an incentive and reward from the beginning of the journey – not only at the end after certification. There is a need to design standard frameworks that are modular ‘improvement plans’, and there is a need for downstream companies to start buying from these producers already at a low stage – i.e. when the producer shows willingness to collaborate and improve, and do so over time. The good news is that ASM standard frameworks are emerging with this approach, e.g. the CRAFT Code, the BGI’s model, and the model of the Fair Cobalt Alliance (FCA).

4. From managing risks only, to looking at generating broader positive impacts

Recent trends have moved the responsible sourcing conversation beyond the OECD DDG’s Annex II and we are now looking at a broader set of issues (e.g. health and safety, environment, etc). But still a lot of effort by mid- and downstream companies is about managing / avoiding these risks and negative impacts. Only a few are also looking at where there are opportunities to create positive impacts. In the future, companies should look to gear their supplier codes of conduct and benchmarks towards favouring suppliers who can show positive improvements. Thinking around what these could be is already out there, in some of the newer standards and the conversation about mining’s contribution to the SDGs, which may involve impacts around: Local procurement, local recruitment, skills development, local SME development, living wages and worker’s rights, renewables use, recycling and circularity, ecological restoration and regeneration etc. Looking at it in this way, with ASM’s large impact on local economic development, including ASM suppliers may become a choice more downstream companies are willing to make.

5. From ‘western’ conversations to global efforts

There is sometimes a lingering accusation that the responsible sourcing agenda is mainly driven by so-called ‘Western’ Governments as well as larger downstream companies in ‘West’.

This is problematic because:

- it makes it easier for certain actors to decry the agenda as ‘neocolonial’,

- it hides the fact that not only the majority of the upstream but also a large part of the mid-stream segments and actors are located outside ‘Western’ markets (and standards and benchmarks are sometimes developed without involving representatives from these geographies), and

- producers, including ASM, already have markets ‘elsewhere’, thus there is an onus to show what they get out of coming into ‘responsible’ chains. Therefore, we need to ensure that this becomes a global effort, and that other markets, economies and countries participate.

6. From isolated issues and sub-sectors to looking at the big picture

There has been a lot of focus on cobalt as a mineral (at least in the battery and automotive space), on ASM as a sub-sector, and on child labour as an issue. While this may help prioritise and serve to satisfy pressure from advocacy groups or tick-box compliance, it may miss the point in the longer term. We need to recognise that there are structural, systemic causes that perpetuate issues such as child labour and a range of other risks, and that there is a need to tackle the root causes (which is only possible if also Governments and others do their part, as mentioned previously). We also need to start thinking beyond the advocacy agenda to other crucial minerals, sub-sectors and issues, such as for example the environmental impacts of nickel mining, water consumption in lithium mining, violence and human rights abuses happening at the hand of security forces around large scale mines, etc, to name just a few.

No one company can do this alone. Collaboration will be key. We are going in the right direction, but there is still much to be done.