At The GIFF Project, putting a political-economy lens to the challenges IFFs present to ASM formalisation reveals three principles, again and again. Firstly, artisanal and small-scale mining is a business. Second, mining begins with the money. Third, formalisation does not happen in a vacuum.

ASM is a business

Gavin Hilson recently enlightened me and other delegates at a meeting of the Africa Minerals Development Centre that it’s taken over twenty years, and enormous policy efforts, for people to think about artisanal mining as a poverty-driven activity.

I am mindful of this as I forge on with this blog. I came to ASM from this perspective, with an emphasis on development and poverty alleviation. I still hold that lens and use it closely, but a profound change in my work came when I started to understand diggers, miners, and all the stakeholders along the supply chain as business people. I think more of us need to apply this lens when we approach ASM formalisation.

At its core, ASM is a business. And the business logic affects how it is structured, how it happens, and who gets to decide how to formalise within it. We must view ASM through both development and business lenses if we are to formalise it.

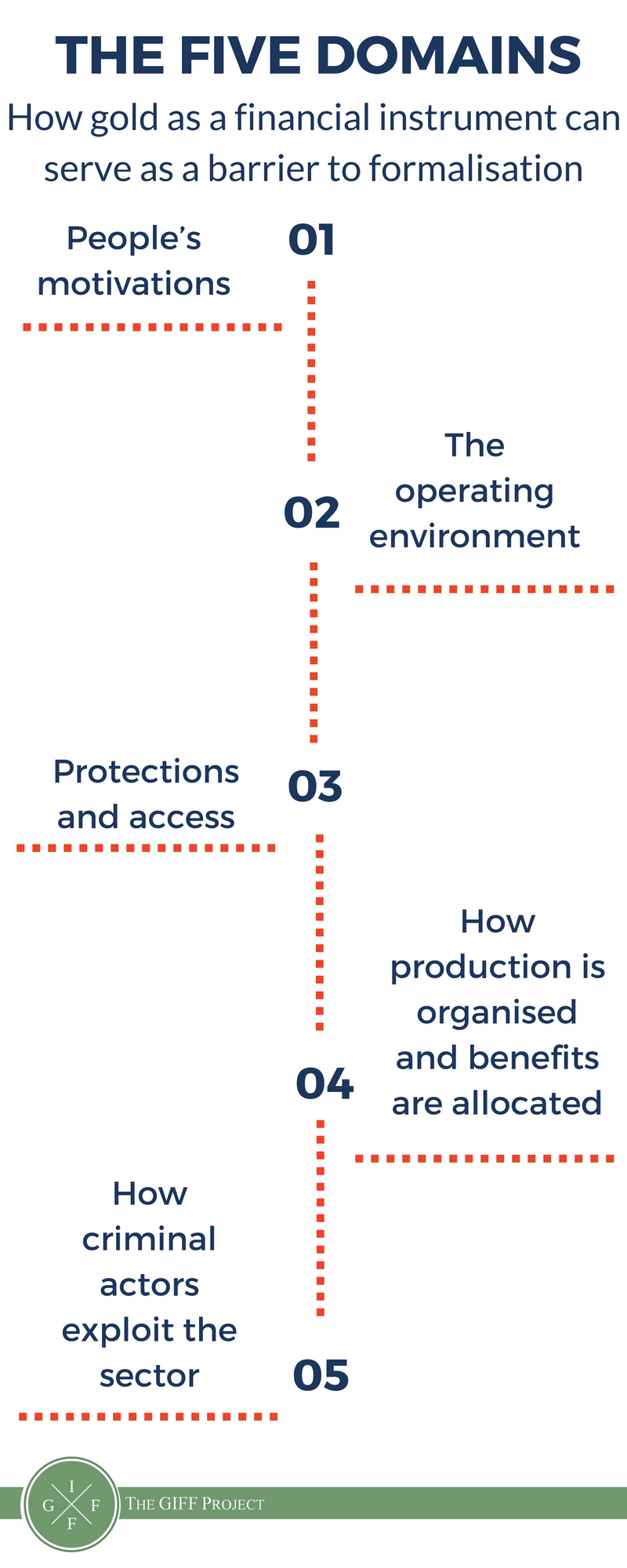

There are five domains that are necessary to understand when considering how gold as a financial instrument can serve as a barrier to formalisation. These are: i) people’s motivations, ii) the operating environment, iii) protections and access, iv) how production is organised and benefits are allocated, and v.) how criminal actors exploit the sector.

1. Motivations matter

Firstly, motivations matter when it comes to formalising a sector. What’s the primary motivation for this person to trade or mine? Is it for survival, profit, or to supplement another income? Is it a profession, an answer to a problem, or a gamble? Is it their primary livelihood, a complementary one, or a supplementary one?

How does it build resilience for the miner/trader as an individual or for their household? Is it their primary or secondary business? Does it serve a commercial or even criminal purpose for the business actor, e.g. money laundering, conflict financing, tax avoidance, currency management, avoidance of formal banking channels, wealth secrecy?

Secondly, what is the operating environment like? Is the policy attitude enabling, tolerant, or adverse to ASM? Is there even a legal framework? Is it fit for purpose, is it appropriate? Is it enforced? Is it feasible and desirable to operate legally, or are miners or traders caught in a grey zone of extra-legality or illegality where they may be subject to predation and harassment by authorities?

What are the land tenure arrangements, the property and mineral rights that must be fulfilled? Who are the impacted stakeholders and what issues or opportunities do they or their actions create? What is the public perception of ASM? Positive or not? Can people take pride in their participation in the sector, or is it shameful?

What options do people have for financing their mining or trading? Who do they turn to for commercial or personal problems? What extension services and subsidised support exists and who offers this? Is it any good?

3. Protections and Access

Thirdly, In terms of the protection economy around ASM, an artisanal miner or their financier must determine how they will secure and protect their access to the resource. In some cases the miner can’t get a license, in other cases s/he may not want to get a license.

In the common scenario of being unlicensed or not operating fully within the law, the miner has to find other ways to protect his/her access to that mineral. Some miners use or threaten violence; it is not uncommon for miners to be armed, especially in contested or remote locations, as I and my colleagues have found on many occasions, for example during our fieldwork on mining in protected areas for ASM-PACE.

Sometimes they protect access using facilitation payments. Sometimes they do it through joint ventures, which is typically a more constructive avenue. These may be international, like Barksanem, or very local, with the chief or the landowner, as is the case in Sierra Leone, for example.

Ultimately, property and mineral rights and land tenure arrangements determine whom the miners or traders might have to pay off, and whether the illegality of the location (such as mining in protected areas or another mining rights-holder’s concession) predetermines the need for facilitation (complicity with corruption) or ‘leave-me-alone’ (a victim of corruption) payments, thereby generating IFFs.

4. Organisation of production and allocation of benefits

Fourthly, how do the miners and their backers organise production? What was the original source of money to start mining, or to scale up or industrialise their mining? Who is in the team, how is it structured, who gets rewarded what? Is that fair? Is there a risk of theft, and therefore having to sell illicitly on the side, creating illicit financial flows?

5. Criminal exploitation

And then, lastly, is the matter of criminality. Criminal actors are the ultimate entrepreneurs, driven by profit. The high-profit and low-risk nature of artisanal mining makes it hugely appealing to criminal groups and actors.

The sector’s informality makes miners vulnerable to exploitation. And the fact of gold being a financial instrument, anonymous and easily transportable, makes it both an easy tool for illicit financial flows, and hard to change.

And when criminal elements are exploiting an ASM situation, certain risks are more likely, and are harder to mitigate, including human trafficking, forced labour, forced displacement, increased environmental damage, links to other flows, and money laundering.

We found with the ASM-PACE project that artisanal miners mining in protected areas have little interest in mining in ways that are environmentally responsible. This is quite understandable yet tragic: in the very places where they need to be most responsible, because they are being chased, they keep moving, augmenting the devastating impacts.

Mining begins with the money

Mining begins with the money: it doesn’t just begin upon picking up a machete, cutting and burning the vegetation, and starting to dig. It begins when the miner decides to mine, and has to get themselves tools and food for subsistence to begin mining, and transportation to get to the mine.

Some miners are independent, using their own money generated by some other business. Other times, they borrow the money, and usually from a businessperson in the community or a local leader. The scale of informal borrowing varies greatly in my experience, from enough to feed the miner for a day to tens of thousands of dollars to tackle a deep or urgent prospect.

So the supply chain does, in a way, begin before the mine: a complex web of financial flows, materialises before gold even leaves the ground and then as the gold moves along the chain also. These webs connect a miner – likely without them realising it, to financial networks around the world. In some cases, illicit financial networks.

Formalisation does not happen in a vacuum

So why does this matter? Governments, regional bodies, and donors are investing millions of dollars in formalisation efforts in numerous countries across the African Great Lakes Region, Western Africa, the Amazonian River Basin, and South East Asia.

The drive for this is primarily coming from the conflict minerals agenda derived from the OECD Due Diligence Guidance, the Kimberley Process and related legislation, as well as the Minimata Convention. But formalisation does not happen in a vacuum and a development agency doesn’t start from scratch. There are structured systems in place and they are working for someone. There are two aspects to this that I think matters.

1. Limitations

First, miners are not necessarily always free to formalise. Miners may not be free to choose to change their behaviour and do things differently. They may find themselves in relationships of economic or social dependency that they will struggle to break.

Some formalisation programs focus on educating the miners, having them understand why they should conform and what the law is. This is important, but may be an utter waste of time, effort and money if you target the miners only or primarily, and don’t take into account these political and financial relations or the commercial prerogatives of the ‘man with the money’.

If you want to formalise ASM, you have to formalise how miners borrow money and how they sell the gold; you have to get the traders on board.

2. Existing structures

Secondly, what’s there already works? We see a huge risk that formalisation efforts are essentially attempting to create a parallel market in a crowded market place, without acknowledging or understanding how powerful, well financed, and well connected their illicit competitors are.

These vested interests will resist change unless their interests are served. If these interests are criminal, it’s unlikely that they will align with the donor or government’s interests! Of course, governments (should) have the force of law but often the real force of the law is fairly weak in resisting these power plays and pressuring them to change, and/or individual agents of the state can complicit with and benefiting from the grey or black economy.

For a formalisation intervention to work it must deal with the reality that it is in competition with sophisticated, functional, and embedded systems that make commercial and political sense, at least for the ones who hold the power and influence.

The GIFF Project: the provision of tools

The GIFF project aims to raise awareness and understanding of IFFs and criminal networks in the supply chains of gold and other precious minerals, with the intention of creating a network of stakeholders who interested in, and working on, artisanal and small scale mining (ASGM) formalisation and IFFs.

The project seeks to strengthen capacity, providing stakeholders and decision makers across sectors with tools to identify, map and address gold IFFs in their gold supply chains. Fieldwork took place in Sierra Leone in July 2016 with GIZ, which is shaping our toolkit and laying the groundwork for a future dialogue there. Dialogues have been organised, and well attended, in Washington D.C. and Paris in 2016.

We will produce three tools for our toolkit in this first phase and are seeking funding for the others. We intend to produce tools targeted to specific stakeholder groups or supply chain operators, so each is better able to identify and manage illicit financial flows in their own domain and given their relationship to the sector and the other relevant actors.

I recently heard the metaphor of the hands on the elephant, in which everyone could individually be touching the same elephant, but with each only touching a part of it - the trunk, or the tail, say - it’s hard to tell what it is. This is similar. Each of the GIFF tools is means by which different stakeholders can put their hand on the elephant. Together, we can then start to understand that elephant, and push it in a certain direction.

Estelle Levin-Nally is the founder and director of Levin Sources. Estelle is also the Director of the GIFF project, a partnership between Levin Sources and the Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime, which is a global network to combat criminal networks, and Director of the ASM-PACE programme, which seeks solutions to mitigate the impacts of artisanal and small-scale mining in protected areas and critical ecosystems.